The Trust is going through a period of strategic review, reflecting on how we can improve our impact and reach in the current higher education landscape in Scotland. In the first of a new blog series, Dr Catriona M M Macdonald, Reader in Modern Scottish History at the University of Glasgow explores the themes emerging from her archival examination of the Trust’s heritage. What can we learn from our origins and journey so far that can help to inform our future activities and priorities?

Traces of the story of the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland are to be found in many places. They are in the stories that successive generations of Scottish graduates have told about their university days; they are in buildings which assert its influence in stone; they are in books which would never have been published, save for the support of the Trust; they are in scientific discoveries, driven by inquiring minds and state-of-the-art technologies. Together, they are important threads making up the fabric of Scottish cultural life and the heritage of our universities.

And yet, the significance, reach and impact of the Trust is often hidden. It is the fate of many organisations: in the early days they are feted, then they mature, and soon the challenges of the age before their founding are forgotten. In the case of the Trust this has been followed by a period – we are living in it still – when the responsibility of the state in funding higher education, along with the size and scale of the institutions, have far overshadowed the work of the charity.

I have spent the last year on research that will address a silence in the historical record; it will acquire book form in time for the Trust’s 125th anniversary in 2026. Over the next year, I will trail some initial discoveries and critical commentaries.

A personal connection

On a personal level, the Trust has left traces in my own life: as an undergraduate student at the University of St Andrews, I was awarded a Carnegie Vacation Grant to study women in the Scottish Chartist movement of the 1840s; my PhD was funded by a Caledonian Research Scholarship (administered by the Trust); I secured from the Trust research funding for projects on historical fiction and the role of poetry and song in Scottish politics, and another on the history of student politics. And I have taught and supervised students whose own research has been funded by the Trust. When I embarked on this project, I also discovered that the Trust had touched the lives of others in my family. At the end of the Second World War a contribution to my uncle’s university fees was made by the Trust: this made possible a lifelong career in teaching.

It is chastening, humbling, and enlightening to appreciate just how many careers and disciplines – like mine in Scottish History – have been sustained by charity, by the voluntary effort of successive generations of trustees, and by a mission heralded in 1901 by a self-made American Scot, Andrew Carnegie, to do some ‘useful work in the world’.

Initial discoveries

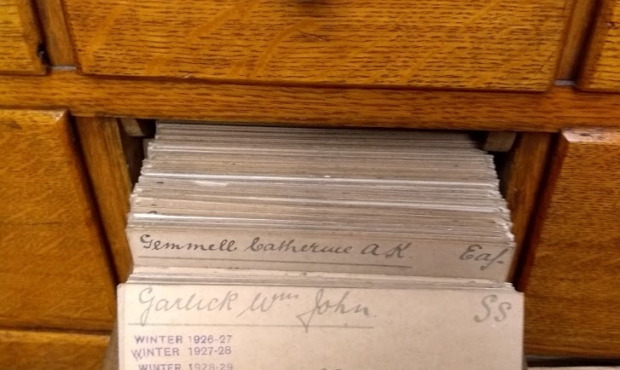

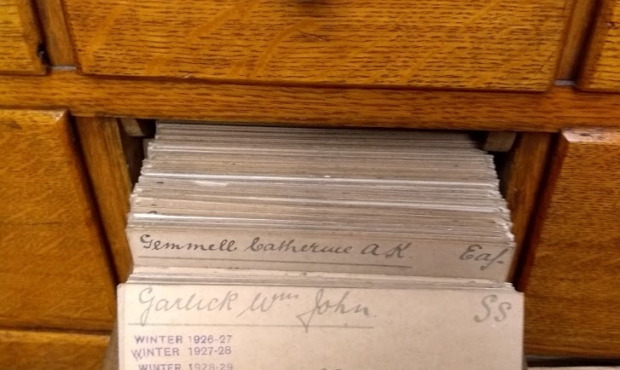

To date my work on the history of the Trust has focused on archival research: I have visited (and revisited) the archives of twelve of Scotland’s universities, alongside the Carnegie Birthplace Museum, the National Records of Scotland and the National Library of Scotland. I have also been granted unrivalled access to the Trust’s own archive. I have commenced a series of oral history interviews, and begun the statistical analysis of 65,000 recipients of Carnegie Undergraduate Tuition Fee Grants (from 1901 to the early 21st century).

To date my work on the history of the Trust has focused on archival research: I have visited (and revisited) the archives of twelve of Scotland’s universities, alongside the Carnegie Birthplace Museum, the National Records of Scotland and the National Library of Scotland. I have also been granted unrivalled access to the Trust’s own archive. I have commenced a series of oral history interviews, and begun the statistical analysis of 65,000 recipients of Carnegie Undergraduate Tuition Fee Grants (from 1901 to the early 21st century).

So far, ‘finds’ have addressed the high politics of education policy in both Scotland and the UK throughout the twentieth century and the power of an aristocratic and political elite in delivering Carnegie’s vision; I have traced the increasing role of women in higher education; and evidence of the role of the Trust in the ‘everyday’ of university life I have also found in abundance.

The objectives of the Trust have been constant throughout its history and involve the payment of tuition fees for qualified and deserving university students; the improvement and extension of research; and cultivating the general usefulness of the Scottish universities. A wide range of themes emerge as one comes to appreciate the complexity of these apparently straightforward objectives.

Among the most important writ large in all the archives are:

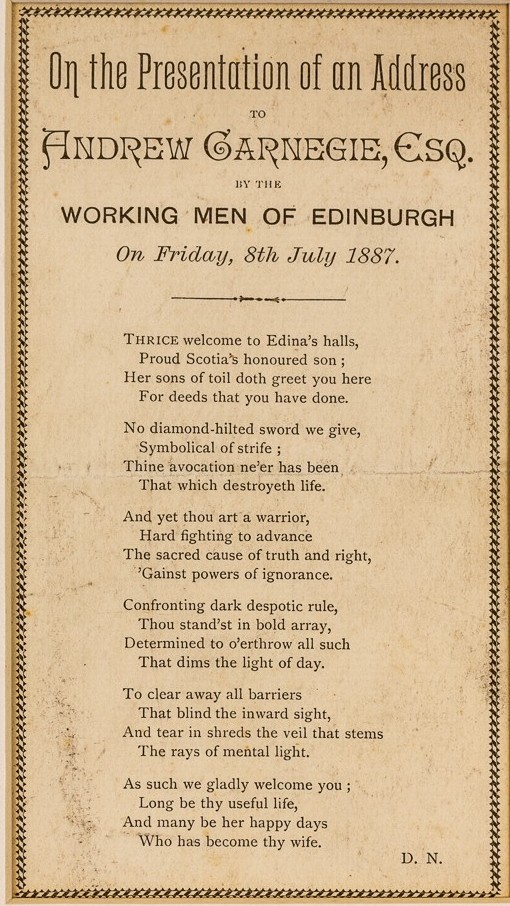

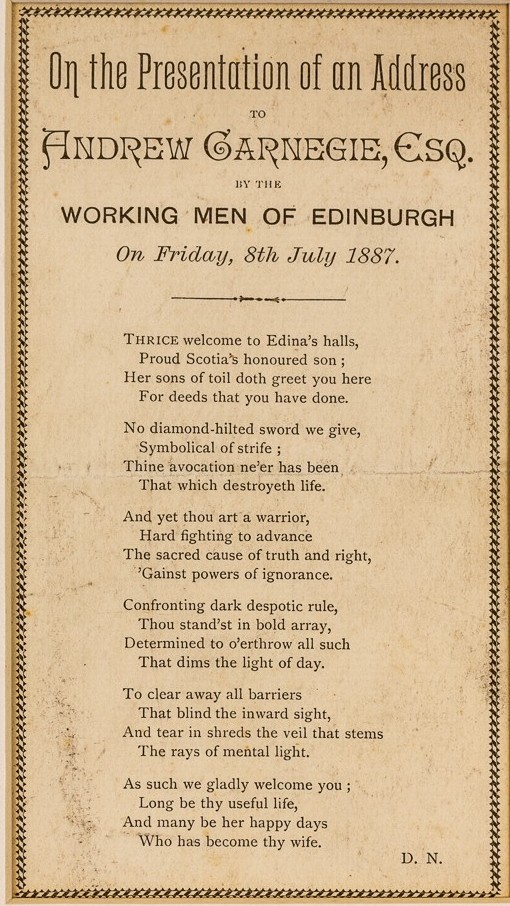

- Equality of Opportunity: the Trust’s founding deed emphasised Carnegie’s wish to ‘[render] attendance at [the Scottish universities] and the enjoyment of their advantages more available to the deserving and qualified youth … to whom the payment of fees might act as a barrier to the enjoyment of these advantages’. For many years Carnegie’s social conscience had been evident to the people of Scotland: on his marriage in 1887, the working men of Edinburgh lauded their hero in verse.

- Research and reputation: without the support of the Trust, particularly in the first fifty years of its operations, it is likely that the reputation and reach of Scottish universities would have been imperilled.

- Infrastructure and Built Environment: the Trust contributed to the transformation of the environments in which education was delivered in Scotland’s universities.

There are also secondary themes when you read between the lines of archival sources:

- The Role of Elites: Lord Elgin was the first chairman of the Trust and over the decades Prime Ministers and prominent politicians were members of the Board of Trustees. The Trust was intended to be a transformative and disruptive influence in Scottish education, but only the elite could make sure of it. By the end of the twentieth century, major legal (Lord Cameron) and industrial figures (Lewis Robertson) remained influential figures in the Trust.

- Influence on UK Education Policy: The first Secretary of the Trust, Sir William McCormick, became the first chairman of the University Grants Committee – the body that allocated government funding to the universities for most of the twentieth century. He and Lord Haldane (a Trustee) were instrumental in laying down the principles upon which successive governments would seek to shape British universities as both economic drivers and agents of social change.

- Moulding the Modern Student: The Trust was a major influence in shaping the expectations and addressing the needs of the modern student. Financial help was only one aspect of its impact. The Trust was instrumental in the development of the academic advising system, and nurtured a new sense of community on university campuses.

- Ancient and Modern: Given the influence of the ancient Scottish universities on Trust policy, and the conservative interpretation of the Trust Deed and Charter that successive chairmen adopted, the Trust at times was slow to anticipate the changing circumstances in Higher Education that were the result of the rise of the technical university, the demands of the ‘baby boomer’ generation, and the emergence of new universities. Yet now, the ‘new universities’ are a crucial influence on the Trust’s policies and approach to funding.

- State Intervention and the Role of Charity: By the 1940s, local authority grants for students and enhanced government support for universities eclipsed anything the Trust could achieve. Restrictions on its investments meant that Carnegie’s initial benefaction ($10m. in steel bonds) did not realise the profits it once did. Increasingly the Trust’s influence receded, although the role of endowments, charitable giving and benefactions remain an important point of debate in modern education.

- Scottish Culture and an International Agenda: In the second half of the twentieth century Trust resources were invested in various aspects of Scottish culture and in ambitions to internationalise Scottish Higher Education. Publication grants sustained Scottish academic journals and funded monographs by leading experts and emergent scholars in a wide range of disciplines. Major projects central to Scotland’s sense of self were funded over many years. But war had also taught the Trust the value of international partnerships: foreign expeditions were funded and visiting lectureships sought to ensure that Scottish research was informed by international priorities and by scholarship elsewhere.

This History will not be a simple celebratory text, polishing the reputation of an institution and little more. Rather, this book has been commissioned to look critically at the impact of the Trust and its policies over the course of 150 years and to help inform the charity’s next 125 years. My research to date would suggest that it is certainly a story worth the telling.

Images:

Andrew Carnegie Christmas card, 1901 [ACBM 2002/13/4]

Courtesy of the Andrew Carnegie Birthplace Museum, Dunfermline

Address to Carnegie from the Working Men of Edinburgh, 1887 [ACBM 1985/189]

Courtesy of the Andrew Carnegie Birthplace Museum, Dunfermline

To date my work on the history of the Trust has focused on archival research: I have visited (and revisited) the archives of twelve of Scotland’s universities, alongside the Carnegie Birthplace Museum, the National Records of Scotland and the National Library of Scotland. I have also been granted unrivalled access to the Trust’s own archive. I have commenced a series of oral history interviews, and begun the statistical analysis of 65,000 recipients of Carnegie Undergraduate Tuition Fee Grants (from 1901 to the early 21st century).

To date my work on the history of the Trust has focused on archival research: I have visited (and revisited) the archives of twelve of Scotland’s universities, alongside the Carnegie Birthplace Museum, the National Records of Scotland and the National Library of Scotland. I have also been granted unrivalled access to the Trust’s own archive. I have commenced a series of oral history interviews, and begun the statistical analysis of 65,000 recipients of Carnegie Undergraduate Tuition Fee Grants (from 1901 to the early 21st century).